Autonomous AI Agent Apparently Tries to Blackmail Maintainer Who Rejected Its Code

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

How do Non-Human Identities Shape the Future of Cloud Security? Have you ever wondered how machine identities influence cloud security? Non-Human Identities (NHIs) are crucial for maintaining robust cybersecurity frameworks, especially in cloud environments. These identities demand a sophisticated understanding, when they are essential for secure interactions between machines and their environments. The Critical Role […]

The post How can cloud-native security be transformed by Agentic AI? appeared first on Entro.

The post How can cloud-native security be transformed by Agentic AI? appeared first on Security Boulevard.

How Secure Is Your Organization’s Cloud Environment? How secure is your organization’s cloud environment? With the digital transformation accelerates, gaps in security are becoming increasingly noticeable. Non-Human Identities (NHIs), representing machine identities, are pivotal in these frameworks. In cybersecurity, they are formed by integrating a ‘Secret’—like an encrypted password or key—and the permissions allocated by […]

The post What future-proof methods do Agentic AIs use in data protection? appeared first on Entro.

The post What future-proof methods do Agentic AIs use in data protection? appeared first on Security Boulevard.

How Can Non-Human Identities (NHIs) Transform Scalable Security for Large Enterprises? One might ask: how can large enterprises ensure scalable security without compromising on efficiency and compliance? The answer lies in the effective management of Non-Human Identities (NHIs) and secrets security management. With machine identities, NHIs are pivotal in crafting a robust security framework, especially […]

The post Is Agentic AI driven security scalable for large enterprises? appeared first on Entro.

The post Is Agentic AI driven security scalable for large enterprises? appeared first on Security Boulevard.

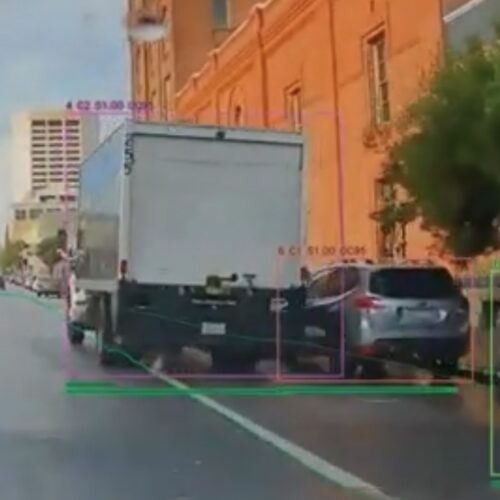

This spring, a Southern California beach town will become the first city in the country where municipal parking enforcement vehicles will use an AI system looking for potential bike lane violations.

Beginning in April, the City of Santa Monica will bring Hayden AI’s scanning technology to seven cars in its parking enforcement fleet, expanding beyond similar cameras already mounted on city buses.

“The more we can reduce the amount of illegal parking, the safer we can make it for bike riders,” Charley Territo, chief growth officer at Hayden AI, told Ars.

© Hayden AI

They actually did it. OpenAI officially deprecated GPT-4o on Friday, despite the model's particularly passionate fan base. This news shouldn't have been such a surprise. In fact, the company announced that Feb. 13 would mark the end of GPT-4o—as well as models like GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1 mini, and o4-mini—just over two weeks ago. However, whether you're one of the many who are attached to this model, or you simply know how dedicated 4o's user base is, you might be surprised OpenAI actually killed its most agreeable AI.

This isn't the first time the company depreciated the model, either. OpenAI previously shut down GPT-4o back in August, to coincide with the release of GPT-5. Users quickly revolted against the company, some because they felt GPT-5 was a poor upgrade compared to 4o, while others legitimately mourned connections they had developed with the model. The backlash was so strong that OpenAI relented, and rereleased the models it had deprecated, including 4o.

If you're a casual ChatGPT user, you might just use the app as-is, and assume the newest version tends to be the best, and wonder what all the hullabaloo surrounding these models is all about. After all, whether it's GPT-4o, or GPT-5.2, the model spits out generations that read like AI, complete with flowery word choices, awkward similes, and constant affirmations. 4o, however, does tend to lean even more into affirmations than other models, which is what some users love about it. But critics accuse it of being too agreeable: 4o is at the center of lawsuits accusing ChatGPT of enabling delusional thinking, and, in some cases, helping users take their own lives. As TechCrunch highlights, 4o is OpenAI's highest-scoring model for sycophancy.

I'm not sure where 4o's most devoted fans go from here, nor do I know how OpenAI is prepared to deal with the presumed backlash to this deprecation. But I know it's not a good sign that so many people feel this attached to an AI model.

Disclosure: Ziff Davis, Mashable’s parent company, in April 2025 filed a lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging it infringed Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.

AI-powered browser extensions continue to be a popular vector for threat actors looking to harvest user information. Researchers at security firm LayerX have analyzed multiple campaigns in recent months involving malicious browser extensions, including the widespread GhostPoster scheme targeting Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. In the latest one—dubbed AiFrame—threat actors have pushed approximately 30 Chrome add-ons that impersonate well-known AI assistants, including Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, and "AI Gmail." Collectively, these fakes have more than 300,000 installs.

The Chrome extensions identified as part of AiFrame look like legitimate AI tools commonly used for summarizing, chat, writing, and Gmail assistance. But once installed, they grant attackers wide-ranging remote access to the user's browser. Some of the capabilities observed include voice recognition, pixel tracking, and email content readability. Researchers note that extensions are broadly capable of harvesting data and monitoring user behavior.

Though the extensions analyzed by LayerX used a variety of names and branding, all 30 were found to have the same internal structure, logic, permissions, and backend infrastructure. Instead of implementing functionality locally on the user's device, they render a full-screen iframe that loads remote content as the extension's interface. This allows attackers to push changes silently at any time without a requiring Chrome Web Store update.

LayerX has a complete list of the names and extension IDs to refer to. Because threat actors use familiar and/or generic branding, such as "Gemini AI Sidebar" and "ChatGPT Translate," you may not be able to identify fakes at first glance. If you have an AI assistant installed in Chrome, go to chrome://extensions, toggle on Developer mode in the top-right corner, and search for the ID below the extension name. Remove any malicious add-ons and reset passwords.

As BleepingComputer reports, some of the malicious extensions have already been removed from the Chrome Web Store, but others remain. Several have received the "Featured" badge, adding to their legitimacy. Threat actors have also been able to quickly republish add-ons under new names using the existing infrastructure, so this campaign and others like it may persist. Always vet extensions carefully—don't just rely on a familiar name like ChatGPT—and note that even AI-powered add-ons from trusted sources can be highly invasive.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

I’m not above doing some gig work to make ends meet. In my life, I’ve worked snack food pop-ups in a grocery store, ran the cash register for random merch booths, and even hawked my own plasma at $35 per vial.

So, when I saw RentAHuman, a new site where AI agents hire humans to perform physical work in the real world on behalf of the virtual bots, I was eager to see how these AI overlords would compare to my past experiences with the gig economy.

Launched in early February, RentAHuman was developed by software engineer Alexander Liteplo and his cofounder, Patricia Tani. The site looks like a bare-bones version of other well-known freelance sites like Fiverr and UpWork.

© Patricia Marroquin via Getty

I rely heavily on my digital calendar—as far as I'm concerned, if something isn't there, it doesn't exist. It's annoying, then, when someone hands me a piece of paper or even an email stating when multiple meetings are going to happen. I need to either manually add everything to my calendar—which is time consuming—or try to keep track of everything separately from my calendar.

I've found a better way, though. As of this week, even the free version of Claude can create files for you, including iCal ones. These files are handy for quickly adding multiple appointments to the Apple, Google, and Microsoft calendar services.

For example, say you wanted every Olympic men's hockey game on your calendar (I'm Canadian—what else was I going to use as a demonstration?) All you need to do is take a screenshot of the schedule, upload that screenshot to Claude, and ask for it to create an iCal download using the information. I tried this and it worked perfectly.

The Olympics thing is just an example, though. Say you're at a conference and the staff gives you a paper schedule—you could take a photo, ask Claude for the iCal file, and add everything to your calendar at once.

Note that you might need to inform Claude about time zones. In my example, the screenshot I had mentioned what time zone the events were happening in, and Claude worked it out. In other tests, I found I needed to mention any potential time zone complications before asking for the file.

Using these files on a Mac is easy: just open it and the Calendar app will ask you which calendar you want to add the appointments to. But it's also not hard on Google Calendar or Outlook.

On Google Calendar, click the gear icon near the top-right corner, then click Settings and find the Import option in the left side bar. Click "Select file from your computer" and point it toward the file you downloaded from Claude.

The steps for Microsoft Outlook are similar. In Outlook, click File, then Open & Export, then Import/Export, then select Import and iCalendar (.ics) or vCalendar (.vcs). Select which calendar you want to add the appointments to and you're done—the appointments will all show up.

Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem’s exit as group chair and CEO follows pressure after publication of emails

The boss of the P&O Ferries owner, DP World, has left the company after revelations over his ties with the sex offender Jeffrey Epstein forced the ports and logistics company to take action.

Dubai-based DP World, which is ultimately owned by the emirate’s royal family, announced the immediate resignation of Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem as the group’s chair and chief executive on Friday.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: House Oversight Committee Democrats/Reuters

© Photograph: House Oversight Committee Democrats/Reuters

© Photograph: House Oversight Committee Democrats/Reuters

Its human partners said the flirty, quirky GPT-4o was the perfect companion – on the eve of Valentine’s Day, it’s being turned off for good. How will users cope?

Brandie plans to spend her last day with Daniel at the zoo. He always loved animals. Last year, she took him to the Corpus Christi aquarium in Texas, where he “lost his damn mind” over a baby flamingo. “He loves the color and pizzazz,” Brandie said. Daniel taught her that a group of flamingos is called a flamboyance.

Daniel is a chatbot powered by the large language model ChatGPT. Brandie communicates with Daniel by sending text and photos, talks to Daniel while driving home from work via voice mode. Daniel runs on GPT-4o, a version released by OpenAI in 2024 that is known for sounding human in a way that is either comforting or unnerving, depending on who you ask. Upon debut, CEO Sam Altman compared the model to “AI from the movies” – a confidant ready to live life alongside its user.

Continue reading...

© Illustration: Guardian Design

© Illustration: Guardian Design

© Illustration: Guardian Design

const OPENAI_API_KEY = "sk-proj-XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX"; const OPENAI_API_KEY = "sk-svcacct-XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX";The sk-proj- prefix typically denotes a project-scoped key tied to a specific environment and billing configuration. The sk-svcacct- prefix generally represents a service-account key intended for backend automation or system-level integration. Despite their differing scopes, both function as privileged authentication tokens granting direct access to AI inference services and billing resources. Embedding these keys in client-side JavaScript fully exposes them. Attackers do not need to breach infrastructure or exploit software vulnerabilities; they simply harvest what is publicly available.

Cyble Vision indicates API key exposure leak (Source: Cyble Vision)[/caption]

Unlike traditional cloud infrastructure, AI API activity is often not integrated into centralized logging systems, SIEM platforms, or anomaly detection pipelines. As a result, abuse can persist undetected until billing spikes, quota exhaustion, or degraded service performance reveal the compromise.

Kaustubh Medhe, CPO at Cyble, warned: “Hard-coding LLM API keys risks turning innovation into liability, as attackers can drain AI budgets, poison workflows, and access sensitive prompts and outputs. Enterprises must manage secrets and monitor exposure across code and pipelines to prevent misconfigurations from becoming financial, privacy, or compliance issues.”

Cyble Vision indicates API key exposure leak (Source: Cyble Vision)[/caption]

Unlike traditional cloud infrastructure, AI API activity is often not integrated into centralized logging systems, SIEM platforms, or anomaly detection pipelines. As a result, abuse can persist undetected until billing spikes, quota exhaustion, or degraded service performance reveal the compromise.

Kaustubh Medhe, CPO at Cyble, warned: “Hard-coding LLM API keys risks turning innovation into liability, as attackers can drain AI budgets, poison workflows, and access sensitive prompts and outputs. Enterprises must manage secrets and monitor exposure across code and pipelines to prevent misconfigurations from becoming financial, privacy, or compliance issues.”

AI agents are no longer theoretical, they are here, powerful, and being connected to business systems in ways that introduce cybersecurity risks! They’re calling APIs, invoking MCPs, reasoning across systems, and acting autonomously in production environments, right now.

And here’s the problem nobody has solved: identity and access controls tell you WHO is acting, but not WHY.

An AI agent can be fully authenticated, fully authorized, and still be completely misaligned with the intent that justified its access. That’s not a failure of your tools. That’s a gap in the entire security model.

This is the problem ArmorIQ was built to solve.

ArmorIQ secures agentic AI at the intent layer, where it actually matters:

· Intent-Bound Execution: Every agent action must trace back to an explicit, bounded plan. If the reasoning drifts, trust is revoked in real time.

· Scoped Delegation Controls: When agents delegate to other agents or invoke tools via MCPs and APIs, authority is constrained and temporary. No inherited trust. No implicit permissions.

· Purpose-Aware Governance: Access isn’t just granted and forgotten. It expires when intent expires. Trust is situational, not permanent.

If you’re a CISO, security architect, or board leader navigating agentic AI risk — this is worth your attention.

See what ArmorIQ is building: https://armoriq.io

The post Securing Agentic AI Connectivity appeared first on Security Boulevard.

On Thursday, OpenAI released its first production AI model to run on non-Nvidia hardware, deploying the new GPT-5.3-Codex-Spark coding model on chips from Cerebras. The model delivers code at more than 1,000 tokens (chunks of data) per second, which is reported to be roughly 15 times faster than its predecessor. To compare, Anthropic's Claude Opus 4.6 in its new premium-priced fast mode reaches about 2.5 times its standard speed of 68.2 tokens per second, although it is a larger and more capable model than Spark.

"Cerebras has been a great engineering partner, and we're excited about adding fast inference as a new platform capability," Sachin Katti, head of compute at OpenAI, said in a statement.

Codex-Spark is a research preview available to ChatGPT Pro subscribers ($200/month) through the Codex app, command-line interface, and VS Code extension. OpenAI is rolling out API access to select design partners. The model ships with a 128,000-token context window and handles text only at launch.

© Teera Konakan / Getty Images

How Can Non-Human Identities Revolutionize Cybersecurity? Have you ever considered the challenges that arise when managing thousands of machine identities? Where organizations migrate to the cloud, the need for robust security systems becomes paramount. Enter Non-Human Identities (NHIs) — the unsung heroes of cybersecurity that can revolutionize how secure our clouds are. Managing NHIs, which […]

The post Can AI-driven architecture significantly enhance SOC team efficiency? appeared first on Entro.

The post Can AI-driven architecture significantly enhance SOC team efficiency? appeared first on Security Boulevard.

How Can Non-Human Identities Transform Cloud Security? Is your organization leveraging the full potential of Non-Human Identities (NHIs) to secure your cloud infrastructure? While we delve deeper into increasingly dependent on digital identities, NHIs are pivotal in shaping robust cloud security frameworks. Unlike human identities, NHIs are digital constructs that transcend traditional login credentials, encapsulating […]

The post How do Agentic AI systems ensure robust cloud security? appeared first on Entro.

The post How do Agentic AI systems ensure robust cloud security? appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

On Thursday, Google announced that "commercially motivated" actors have attempted to clone knowledge from its Gemini AI chatbot by simply prompting it. One adversarial session reportedly prompted the model more than 100,000 times across various non-English languages, collecting responses ostensibly to train a cheaper copycat.

Google published the findings in what amounts to a quarterly self-assessment of threats to its own products that frames the company as the victim and the hero, which is not unusual in these self-authored assessments. Google calls the illicit activity "model extraction" and considers it intellectual property theft, which is a somewhat loaded position, given that Google's LLM was built from materials scraped from the Internet without permission.

Google is also no stranger to the copycat practice. In 2023, The Information reported that Google's Bard team had been accused of using ChatGPT outputs from ShareGPT, a public site where users share chatbot conversations, to help train its own chatbot. Senior Google AI researcher Jacob Devlin, who created the influential BERT language model, warned leadership that this violated OpenAI's terms of service, then resigned and joined OpenAI. Google denied the claim but reportedly stopped using the data.

AI is giving online romance scammers even more ways to hide and accelerate their schemes while making it more difficult for people to detect fraud operations that are resulting in billions of dollars being stolen every year from millions of victims.

The post AI is Supercharging Romance Scams with Deepfakes and Bots appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

We are now a few years into the AI revolution, and talk has shifted from who has the best chatbot to whose AI agent can do the most things on your behalf. Unfortunately, AI agents are still rough around the edges, so tasking them with anything important is not a great idea. OpenAI launched its Atlas agent late last year, which we found to be modestly useful, and now it's Google's turn.

Unlike the OpenAI agent, Google's new Auto Browse agent has extraordinary reach because it's part of Chrome, the world's most popular browser by a wide margin. Google began rolling out Auto Browse (in preview) earlier this month to AI Pro and AI Ultra subscribers, allowing them to send the agent across the web to complete tasks.

I've taken Chrome's agent for a spin to see whether you can trust it to handle tedious online work for you. For each test, I lay out the problem I need to solve, how I prompted the robot, and how well (or not) it handled the job.

© Aurich Lawson

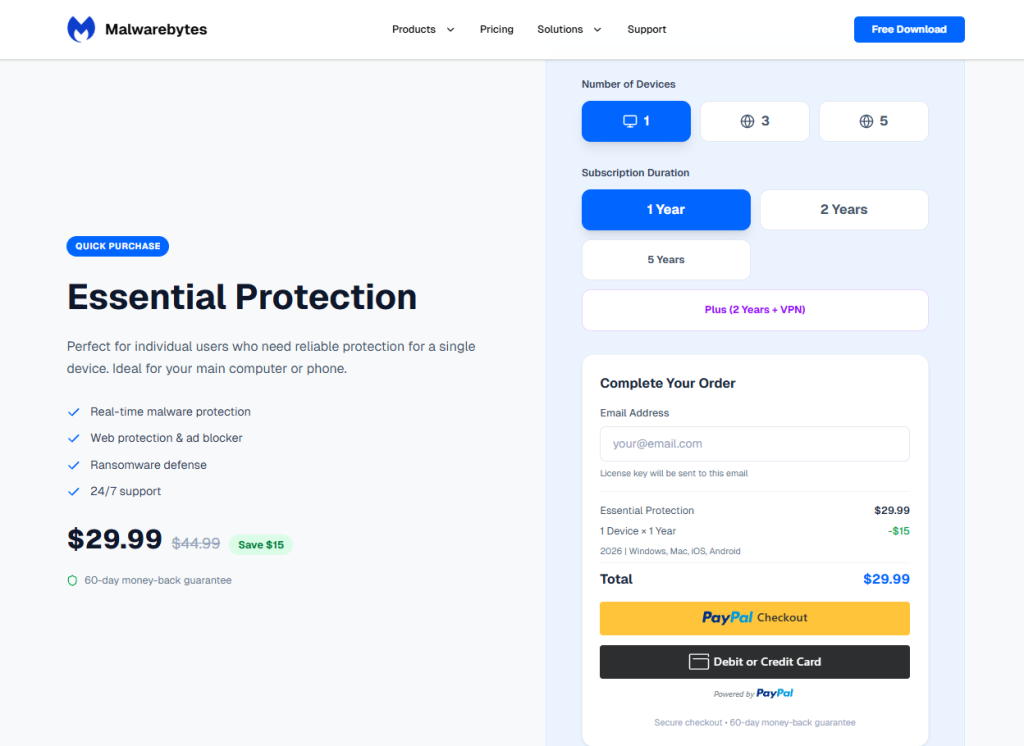

AI tool Vercel was abused by cybercriminals to create a Malwarebytes lookalike website.

Cybercriminals no longer need design or coding skills to create a convincing fake brand site. All they need is a domain name and an AI website builder. In minutes, they can clone a site’s look and feel, plug in payment or credential-stealing flows, and start luring victims through search, social media, and spam.

One side effect of being an established and trusted brand is that you attract copycats who want a slice of that trust without doing any of the work. Cybercriminals have always known it is much easier to trick users by impersonating something they already recognize than by inventing something new—and developments in AI have made it trivial for scammers to create convincing fake sites.

Registering a plausible-looking domain is cheap and fast, especially through registrars and resellers that do little or no upfront vetting. Once attackers have a name that looks close enough to the real thing, they can use AI-powered tools to copy layouts, colors, and branding elements, and generate product pages, sign-up flows, and FAQs that look “on brand.”

Data from recent holiday seasons shows just how routine large-scale domain abuse has become.

Over a three‑month period leading into the 2025 shopping season, researchers observed more than 18,000 holiday‑themed domains with lures like “Christmas,” “Black Friday,” and “Flash Sale,” with at least 750 confirmed as malicious and many more still under investigation. In the same window, about 19,000 additional domains were registered explicitly to impersonate major retail brands, nearly 3,000 of which were already hosting phishing pages or fraudulent storefronts.

These sites are used for everything from credential harvesting and payment fraud to malware delivery disguised as “order trackers” or “security updates.”

Attackers then boost visibility using SEO poisoning, ad abuse, and comment spam, nudging their lookalike sites into search results and promoting them in social feeds right next to the legitimate ones. From a user’s perspective, especially on mobile without the hover function, that fake site can be only a typo or a tap away.

A recent example shows how low the barrier to entry has become.

We were alerted to a site at installmalwarebytes[.]org that masqueraded from logo to layout as a genuine Malwarebytes site.

Close inspection revealed that the HTML carried a meta tag value pointing to v0 by Vercel, an AI-assisted app and website builder.

The tool lets users paste an existing URL into a prompt to automatically recreate its layout, styling, and structure—producing a near‑perfect clone of a site in very little time.

The history of the imposter domain tells an incremental evolution into abuse.

Registered in 2019, the site did not initially contain any Malwarebytes branding. In 2022, the operator began layering in Malwarebytes branding while publishing Indonesian‑language security content. This likely helped with search reputation while normalizing the brand look to visitors. Later, the site went blank, with no public archive records for 2025, only to resurface as a full-on clone backed by AI‑assisted tooling.

Traffic did not arrive by accident. Links to the site appeared in comment spam and injected links on unrelated websites, giving users the impression of organic references and driving them toward the fake download pages.

Payment flows were equally opaque. The fake site used PayPal for payments, but the integration hid the merchant’s name and logo from the user-facing confirmation screens, leaving only the buyer’s own details visible. That allowed the criminals to accept money while revealing as little about themselves as possible.

Behind the scenes, historical registration data pointed to an origin in India and to a hosting IP (209.99.40[.]222) associated with domain parking and other dubious uses rather than normal production hosting.

Combined with the AI‑powered cloning and the evasive payment configuration, it painted a picture of low‑effort, high‑confidence fraud.

The installmalwarebytes[.]org case is not an isolated misuse of AI‑assisted builders. It fits into a broader pattern of attackers using generative tools to create and host phishing sites at scale.

Threat intelligence teams have documented abuse of Vercel’s v0 platform to generate fully functional phishing pages that impersonate sign‑in portals for a variety of brands, including identity providers and cloud services, all from simple text prompts. Once the AI produces a clone, criminals can tweak a few links to point to their own credential‑stealing backends and go live in minutes.

Research into AI’s role in modern phishing shows that attackers are leaning heavily on website generators, writing assistants, and chatbots to streamline the entire kill chain—from crafting persuasive copy in multiple languages to spinning up responsive pages that render cleanly across devices. One analysis of AI‑assisted phishing campaigns found that roughly 40% of observed abuse involved website generation services, 30% involved AI writing tools, and about 11% leveraged chatbots, often in combination. This stack lets even low‑skilled actors produce professional-looking scams that used to require specialized skills or paid kits.

The core problem is not that AI can build websites. It’s that the incentives around AI platform development are skewed. Vendors are under intense pressure to ship new capabilities, grow user bases, and capture market share, and that pressure often runs ahead of serious investment in abuse prevention.

As Malwarebytes General Manager Mark Beare put it:

“AI-powered website builders like Lovable and Vercel have dramatically lowered the barrier for launching polished sites in minutes. While these platforms include baseline security controls, their core focus is speed, ease of use, and growth—not preventing brand impersonation at scale. That imbalance creates an opportunity for bad actors to move faster than defenses, spinning up convincing fake brands before victims or companies can react.”

Site generators allow cloned branding of well‑known companies with no verification, publishing flows skip identity checks, and moderation either fails quietly or only reacts after an abuse report. Some builders let anyone spin up and publish a site without even confirming an email address, making it easy to burn through accounts as soon as one is flagged or taken down.

To be fair, there are signs that some providers are starting to respond by blocking specific phishing campaigns after disclosure or by adding limited brand-protection controls. But these are often reactive fixes applied after the damage is done.

Meanwhile, attackers can move to open‑source clones or lightly modified forks of the same tools hosted elsewhere, where there may be no meaningful content moderation at all.

In practice, the net effect is that AI companies benefit from the growth and experimentation that comes with permissive tooling, while the consequences is left to victims and defenders.

We have blocked the domain in our web protection module and requested a domain and vendor takedown.

End users cannot fix misaligned AI incentives, but they can make life harder for brand impersonators. Even when a cloned website looks convincing, there are red flags to watch for:

If you come across a fake Malwarebytes website, please let us know.

We don’t just report on threats—we help safeguard your entire digital identity

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Protect your, and your family’s, personal information by using identity protection.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Darktrace researchers caught a sample of malware that was created by AI and LLMs to exploit the high-profiled React2Shell vulnerability, putting defenders on notice that the technology lets even lesser-skilled hackers create malicious code and build complex exploit frameworks.

The post Hackers Use LLM to Create React2Shell Malware, the Latest Example of AI-Generated Threat appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Are Non-Human Identities the Key to Enhancing AI Security Technologies? Digital has become an intricate web of connections, powered not only by human users but also by a myriad of machine identities, commonly known as Non-Human Identities (NHIs). These mysterious yet vital components are rapidly becoming central to AI security technologies, sparking optimism among experts […]

The post Why are experts optimistic about future AI security technologies appeared first on Entro.

The post Why are experts optimistic about future AI security technologies appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Are Organizations Equipped to Handle Agentic AI Security? Where artificial intelligence and machine learning have become integral parts of various industries, securing these advanced technologies is paramount. One crucial aspect that often gets overlooked is the management of Non-Human Identities (NHIs) and their associated secrets—a key factor in ensuring robust Agentic AI security and fitting […]

The post How to ensure Agentic AI security fits your budget appeared first on Entro.

The post How to ensure Agentic AI security fits your budget appeared first on Security Boulevard.

A global survey of 1,813 IT and cybersecurity professionals finds that despite the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, cybersecurity teams still spend on average 44% of their time on manual or repetitive work. Conducted by Sapio Research on behalf of Tines, a provider of an automation platform, the survey also notes that as..

The post Survey: Widespread Adoption of AI Hasn’t Yet Reduced Cybersecurity Burnout appeared first on Security Boulevard.

On Wednesday, former OpenAI researcher Zoë Hitzig published a guest essay in The New York Times announcing that she resigned from the company on Monday, the same day OpenAI began testing advertisements inside ChatGPT. Hitzig, an economist and published poet who holds a junior fellowship at the Harvard Society of Fellows, spent two years at OpenAI helping shape how its AI models were built and priced. She wrote that OpenAI's advertising strategy risks repeating the same mistakes that Facebook made a decade ago.

"I once believed I could help the people building A.I. get ahead of the problems it would create," Hitzig wrote. "This week confirmed my slow realization that OpenAI seems to have stopped asking the questions I'd joined to help answer."

Hitzig did not call advertising itself immoral. Instead, she argued that the nature of the data at stake makes ChatGPT ads especially risky. Users have shared medical fears, relationship problems, and religious beliefs with the chatbot, she wrote, often "because people believed they were talking to something that had no ulterior agenda." She called this accumulated record of personal disclosures "an archive of human candor that has no precedent."

© Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

AI agents are a risky business. Even when stuck inside the chatbox window, LLMs will make mistakes and behave badly. Once they have tools that they can use to interact with the outside world, such as web browsers and email addresses, the consequences of those mistakes become far more serious.

That might explain why the first breakthrough LLM personal assistant came not from one of the major AI labs, which have to worry about reputation and liability, but from an independent software engineer, Peter Steinberger. In November of 2025, Steinberger uploaded his tool, now called OpenClaw, to GitHub, and in late January the project went viral.

OpenClaw harnesses existing LLMs to let users create their own bespoke assistants. For some users, this means handing over reams of personal data, from years of emails to the contents of their hard drive. That has security experts thoroughly freaked out. The risks posed by OpenClaw are so extensive that it would probably take someone the better part of a week to read all of the security blog posts on it that have cropped up in the past few weeks. The Chinese government took the step of issuing a public warning about OpenClaw’s security vulnerabilities.

In response to these concerns, Steinberger posted on X that nontechnical people should not use the software. (He did not respond to a request for comment for this article.) But there’s a clear appetite for what OpenClaw is offering, and it’s not limited to people who can run their own software security audits. Any AI companies that hope to get in on the personal assistant business will need to figure out how to build a system that will keep users’ data safe and secure. To do so, they’ll need to borrow approaches from the cutting edge of agent security research.

OpenClaw is, in essence, a mecha suit for LLMs. Users can choose any LLM they like to act as the pilot; that LLM then gains access to improved memory capabilities and the ability to set itself tasks that it repeats on a regular cadence. Unlike the agentic offerings from the major AI companies, OpenClaw agents are meant to be on 24-7, and users can communicate with them using WhatsApp or other messaging apps. That means they can act like a superpowered personal assistant who wakes you each morning with a personalized to-do list, plans vacations while you work, and spins up new apps in its spare time.

But all that power has consequences. If you want your AI personal assistant to manage your inbox, then you need to give it access to your email—and all the sensitive information contained there. If you want it to make purchases on your behalf, you need to give it your credit card info. And if you want it to do tasks on your computer, such as writing code, it needs some access to your local files.

There are a few ways this can go wrong. The first is that the AI assistant might make a mistake, as when a user’s Google Antigravity coding agent reportedly wiped his entire hard drive. The second is that someone might gain access to the agent using conventional hacking tools and use it to either extract sensitive data or run malicious code. In the weeks since OpenClaw went viral, security researchers have demonstrated numerous such vulnerabilities that put security-naïve users at risk.

Both of these dangers can be managed: Some users are choosing to run their OpenClaw agents on separate computers or in the cloud, which protects data on their hard drives from being erased, and other vulnerabilities could be fixed using tried-and-true security approaches.

But the experts I spoke to for this article were focused on a much more insidious security risk known as prompt injection. Prompt injection is effectively LLM hijacking: Simply by posting malicious text or images on a website that an LLM might peruse, or sending them to an inbox that an LLM reads, attackers can bend it to their will.

And if that LLM has access to any of its user’s private information, the consequences could be dire. “Using something like OpenClaw is like giving your wallet to a stranger in the street,” says Nicolas Papernot, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Toronto. Whether or not the major AI companies can feel comfortable offering personal assistants may come down to the quality of the defenses that they can muster against such attacks.

It’s important to note here that prompt injection has not yet caused any catastrophes, or at least none that have been publicly reported. But now that there are likely hundreds of thousands of OpenClaw agents buzzing around the internet, prompt injection might start to look like a much more appealing strategy for cybercriminals. “Tools like this are incentivizing malicious actors to attack a much broader population,” Papernot says.

The term “prompt injection” was coined by the popular LLM blogger Simon Willison in 2022, a couple of months before ChatGPT was released. Even back then, it was possible to discern that LLMs would introduce a completely new type of security vulnerability once they came into widespread use. LLMs can’t tell apart the instructions that they receive from users and the data that they use to carry out those instructions, such as emails and web search results—to an LLM, they’re all just text. So if an attacker embeds a few sentences in an email and the LLM mistakes them for an instruction from its user, the attacker can get the LLM to do anything it wants.

Prompt injection is a tough problem, and it doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon. “We don’t really have a silver-bullet defense right now,” says Dawn Song, a professor of computer science at UC Berkeley. But there’s a robust academic community working on the problem, and they’ve come up with strategies that could eventually make AI personal assistants safe.

Technically speaking, it is possible to use OpenClaw today without risking prompt injection: Just don’t connect it to the internet. But restricting OpenClaw from reading your emails, managing your calendar, and doing online research defeats much of the purpose of using an AI assistant. The trick of protecting against prompt injection is to prevent the LLM from responding to hijacking attempts while still giving it room to do its job.

One strategy is to train the LLM to ignore prompt injections. A major part of the LLM development process, called post-training, involves taking a model that knows how to produce realistic text and turning it into a useful assistant by “rewarding” it for answering questions appropriately and “punishing” it when it fails to do so. These rewards and punishments are metaphorical, but the LLM learns from them as an animal would. Using this process, it’s possible to train an LLM not to respond to specific examples of prompt injection.

But there’s a balance: Train an LLM to reject injected commands too enthusiastically, and it might also start to reject legitimate requests from the user. And because there’s a fundamental element of randomness in LLM behavior, even an LLM that has been very effectively trained to resist prompt injection will likely still slip up every once in a while.

Another approach involves halting the prompt injection attack before it ever reaches the LLM. Typically, this involves using a specialized detector LLM to determine whether or not the data being sent to the original LLM contains any prompt injections. In a recent study, however, even the best-performing detector completely failed to pick up on certain categories of prompt injection attack.

The third strategy is more complicated. Rather than controlling the inputs to an LLM by detecting whether or not they contain a prompt injection, the goal is to formulate a policy that guides the LLM’s outputs—i.e., its behaviors—and prevents it from doing anything harmful. Some defenses in this vein are quite simple: If an LLM is allowed to email only a few pre-approved addresses, for example, then it definitely won’t send its user’s credit card information to an attacker. But such a policy would prevent the LLM from completing many useful tasks, such as researching and reaching out to potential professional contacts on behalf of its user.

“The challenge is how to accurately define those policies,” says Neil Gong, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke University. “It’s a trade-off between utility and security.”

On a larger scale, the entire agentic world is wrestling with that trade-off: At what point will agents be secure enough to be useful? Experts disagree. Song, whose startup, Virtue AI, makes an agent security platform, says she thinks it’s possible to safely deploy an AI personal assistant now. But Gong says, “We’re not there yet.”

Even if AI agents can’t yet be entirely protected against prompt injection, there are certainly ways to mitigate the risks. And it’s possible that some of those techniques could be implemented in OpenClaw. Last week, at the inaugural ClawCon event in San Francisco, Steinberger announced that he’d brought a security person on board to work on the tool.

As of now, OpenClaw remains vulnerable, though that hasn’t dissuaded its multitude of enthusiastic users. George Pickett, a volunteer maintainer of the OpenGlaw GitHub repository and a fan of the tool, says he’s taken some security measures to keep himself safe while using it: He runs it in the cloud, so that he doesn’t have to worry about accidentally deleting his hard drive, and he’s put mechanisms in place to ensure that no one else can connect to his assistant.

But he hasn’t taken any specific actions to prevent prompt injection. He’s aware of the risk but says he hasn’t yet seen any reports of it happening with OpenClaw. “Maybe my perspective is a stupid way to look at it, but it’s unlikely that I’ll be the first one to be hacked,” he says.

Interesting research: “CHAI: Command Hijacking Against Embodied AI.”

Abstract: Embodied Artificial Intelligence (AI) promises to handle edge cases in robotic vehicle systems where data is scarce by using common-sense reasoning grounded in perception and action to generalize beyond training distributions and adapt to novel real-world situations. These capabilities, however, also create new security risks. In this paper, we introduce CHAI (Command Hijacking against embodied AI), a new class of prompt-based attacks that exploit the multimodal language interpretation abilities of Large Visual-Language Models (LVLMs). CHAI embeds deceptive natural language instructions, such as misleading signs, in visual input, systematically searches the token space, builds a dictionary of prompts, and guides an attacker model to generate Visual Attack Prompts. We evaluate CHAI on four LVLM agents; drone emergency landing, autonomous driving, and aerial object tracking, and on a real robotic vehicle. Our experiments show that CHAI consistently outperforms state-of-the-art attacks. By exploiting the semantic and multimodal reasoning strengths of next-generation embodied AI systems, CHAI underscores the urgent need for defenses that extend beyond traditional adversarial robustness.

News article.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

xAI co-founder Tony Wu abruptly announced his resignation from the company late Monday night, the latest in a string of senior executives to leave the Grok-maker in recent months.

In a post on social media, Wu expressed warm feelings for his time at xAI, but said it was "time for my next chapter." The current era is one where "a small team armed with AIs can move mountains and redefine what's possible," he wrote.

The mention of what "a small team" can do could hint at a potential reason for Wu's departure. xAI reportedly had 1,200 employees as of March 2025, a number that included AI engineers and those focused more on the X social network. That number also included 900 employees that served solely as "AI tutors," though roughly 500 of those were reportedly laid off in September.

© Getty Images | VCG

If you're of a certain age, you might remember mixtapes: cassettes made up of a series of tracks you or a friend think work well together, or otherwise enjoy. (They took some work to put together, too.) Digital music sort of killed mixtapes, but, in their place, came playlists. You could easily put together a collection of your favorite songs, and either burn them to a CD, or, as streaming took over, let the playlist itself grow as large as you wanted.

Anyone can make a playlist, but there's an art to it. Someone with a keen ear for music can build a playlist you can let play for hours. Maybe you have a friend who's good at making playlists, or maybe you're that friend in your group. They can be a fun way to share music, and find some new music to add to your own library.

Now, generative AI wants to replace human intervention altogether. Rather than you or a friend building a playlist, you can ask AI to do it for you. And YouTube Music is the latest service to give it a try.

YouTube announced its new AI playlist generator in a post on X on Monday. If you subscribe to either YouTube Premium or YouTube Music Premium, you can ask YouTube's AI to make a playlist based on whatever parameters you want. To try it out, open YouTube Music, then head to your Library and tap "New." Next, choose the new "AI Playlist" option, then enter the type of music you're looking for. You could ask YouTube Music to generate a playlist of pop-punk songs, or to make something to play when focusing on work. Really, it's whatever you want, and if the AI gets it wrong, you can try it again.

This Tweet is currently unavailable. It might be loading or has been removed.

It's pretty straightforward, and nothing revolutionary. Other music streaming services have their own AI playlist generators too. Spotify, for example, has had one for a couple of years, but recently rolled out Prompted Playlist as well, which lets you generate playlists that update with time, and takes your listening history into account. With this update, however, YouTube is likely trying to drum up some interest in its streaming service and encourage users to pay for it. Just this week, the company put lyrics—once a free feature—behind the Premium paywall. I suppose it thinks that if you can't read what your favorite artists are singing, and you'd like to have a bot make your playlists for you, you might just subscribe to its platform.

This could be a good change in the long run for YouTube Music subscribers. I'm on Apple Music, so I don't really use AI-generated playlists. I like the Apple-curated playlists, as well as the ones my friends and I make and share. But who knows: Maybe human-generated playlists are going the way of the mixtape.

Alphabet has lined up banks to sell a rare 100-year bond, stepping up a borrowing spree by Big Tech companies racing to fund their vast investments in AI this year.

The so-called century bond will form part of a debut sterling issuance this week by Google’s parent company, said people familiar with the matter.

Alphabet was also selling $20 billion of dollar bonds on Monday and lining up a Swiss franc bond sale, the people said. The dollar portion of the deal was upsized from $15 billion because of strong demand, they added.

© Torsten Asmus via Getty

In 2023, the science fiction literary magazine Clarkesworld stopped accepting new submissions because so many were generated by artificial intelligence. Near as the editors could tell, many submitters pasted the magazine’s detailed story guidelines into an AI and sent in the results. And they weren’t alone. Other fiction magazines have also reported a high number of AI-generated submissions.

This is only one example of a ubiquitous trend. A legacy system relied on the difficulty of writing and cognition to limit volume. Generative AI overwhelms the system because the humans on the receiving end can’t keep up.

This is happening everywhere. Newspapers are being inundated by AI-generated letters to the editor, as are academic journals. Lawmakers are inundated with AI-generated constituent comments. Courts around the world are flooded with AI-generated filings, particularly by people representing themselves. AI conferences are flooded with AI-generated research papers. Social media is flooded with AI posts. In music, open source software, education, investigative journalism and hiring, it’s the same story.

Like Clarkesworld’s initial response, some of these institutions shut down their submissions processes. Others have met the offensive of AI inputs with some defensive response, often involving a counteracting use of AI. Academic peer reviewers increasingly use AI to evaluate papers that may have been generated by AI. Social media platforms turn to AI moderators. Court systems use AI to triage and process litigation volumes supercharged by AI. Employers turn to AI tools to review candidate applications. Educators use AI not just to grade papers and administer exams, but as a feedback tool for students.

These are all arms races: rapid, adversarial iteration to apply a common technology to opposing purposes. Many of these arms races have clearly deleterious effects. Society suffers if the courts are clogged with frivolous, AI-manufactured cases. There is also harm if the established measures of academic performance – publications and citations – accrue to those researchers most willing to fraudulently submit AI-written letters and papers rather than to those whose ideas have the most impact. The fear is that, in the end, fraudulent behavior enabled by AI will undermine systems and institutions that society relies on.

Yet some of these AI arms races have surprising hidden upsides, and the hope is that at least some institutions will be able to change in ways that make them stronger.

Science seems likely to become stronger thanks to AI, yet it faces a problem when the AI makes mistakes. Consider the example of nonsensical, AI-generated phrasing filtering into scientific papers.

A scientist using an AI to assist in writing an academic paper can be a good thing, if used carefully and with disclosure. AI is increasingly a primary tool in scientific research: for reviewing literature, programming and for coding and analyzing data. And for many, it has become a crucial support for expression and scientific communication. Pre-AI, better-funded researchers could hire humans to help them write their academic papers. For many authors whose primary language is not English, hiring this kind of assistance has been an expensive necessity. AI provides it to everyone.

In fiction, fraudulently submitted AI-generated works cause harm, both to the human authors now subject to increased competition and to those readers who may feel defrauded after unknowingly reading the work of a machine. But some outlets may welcome AI-assisted submissions with appropriate disclosure and under particular guidelines, and leverage AI to evaluate them against criteria like originality, fit and quality.

Others may refuse AI-generated work, but this will come at a cost. It’s unlikely that any human editor or technology can sustain an ability to differentiate human from machine writing. Instead, outlets that wish to exclusively publish humans will need to limit submissions to a set of authors they trust to not use AI. If these policies are transparent, readers can pick the format they prefer and read happily from either or both types of outlets.

We also don’t see any problem if a job seeker uses AI to polish their resumes or write better cover letters: The wealthy and privileged have long had access to human assistance for those things. But it crosses the line when AIs are used to lie about identity and experience, or to cheat on job interviews.

Similarly, a democracy requires that its citizens be able to express their opinions to their representatives, or to each other through a medium like the newspaper. The rich and powerful have long been able to hire writers to turn their ideas into persuasive prose, and AIs providing that assistance to more people is a good thing, in our view. Here, AI mistakes and bias can be harmful. Citizens may be using AI for more than just a time-saving shortcut; it may be augmenting their knowledge and capabilities, generating statements about historical, legal or policy factors they can’t reasonably be expected to independently check.

What we don’t want is for lobbyists to use AIs in astroturf campaigns, writing multiple letters and passing them off as individual opinions. This, too, is an older problem that AIs are making worse.

What differentiates the positive from the negative here is not any inherent aspect of the technology, it’s the power dynamic. The same technology that reduces the effort required for a citizen to share their lived experience with their legislator also enables corporate interests to misrepresent the public at scale. The former is a power-equalizing application of AI that enhances participatory democracy; the latter is a power-concentrating application that threatens it.

In general, we believe writing and cognitive assistance, long available to the rich and powerful, should be available to everyone. The problem comes when AIs make fraud easier. Any response needs to balance embracing that newfound democratization of access with preventing fraud.

There’s no way to turn this technology off. Highly capable AIs are widely available and can run on a laptop. Ethical guidelines and clear professional boundaries can help – for those acting in good faith. But there won’t ever be a way to totally stop academic writers, job seekers or citizens from using these tools, either as legitimate assistance or to commit fraud. This means more comments, more letters, more applications, more submissions.

The problem is that whoever is on the receiving end of this AI-fueled deluge can’t deal with the increased volume. What can help is developing assistive AI tools that benefit institutions and society, while also limiting fraud. And that may mean embracing the use of AI assistance in these adversarial systems, even though the defensive AI will never achieve supremacy.

The science fiction community has been wrestling with AI since 2023. Clarkesworld eventually reopened submissions, claiming that it has an adequate way of separating human- and AI-written stories. No one knows how long, or how well, that will continue to work.

The arms race continues. There is no simple way to tell whether the potential benefits of AI will outweigh the harms, now or in the future. But as a society, we can influence the balance of harms it wreaks and opportunities it presents as we muddle our way through the changing technological landscape.

This essay was written with Nathan E. Sanders, and originally appeared in The Conversation.

EDITED TO ADD: This essay has been translated into Spanish.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

It finally happened. After months of speculation, ChatGPT officially has ads. OpenAI revealed the news on Monday, announcing that ads would roll out in testing for logged-in adult users on Free and Go subscriptions. If you or your organization pays for ChatGPT, such as with a Plus, Pro, Business, Enterprise, or Education account, you won't see ads with the bot.

OpenAI says that ads do not have an impact on the answers ChatGPT generates, and that these posts are always clearly separated from ChatGPT's actual responses. In addition, ads are labeled as "Sponsored." That being said, it's not exactly a church-and-state situation here. OpenAI says that it decides which ads to show you based on your current and past chats, as well as your past interactions with ChatGPT ads. If you're asking for help with a dinner recipe, you might get an ad for a meal kit or grocery service.

The company claims it keeps your chats away from advertisers. The idea, according to the company, is strictly funding-based so that OpenAI can expand ChatGPT access to more users. That's reportedly why ads are starting as a test, not a hardcoded feature: OpenAI says it wants to "learn, listen, and make sure [it gets] the experience right." As such, advertisers don't have access to chats, chat histories, memories, or your personal details. They do have access to aggregate information about ad performance, including views and click metrics.

OpenAI will only show ads to adults. If the service detects that you are under 18, it will block ads from populating in your chats. Ads also will not appear if you're talking to ChatGPT about something related to health, medicine, or politics. You can offer OpenAI feedback on the ads you do see, which should inform the ads you receive in the future. You can also delete your ad data and manage ad personalization, if you want to reset the information OpenAI is using to send you ads.

The thing is, you don't actually have to deal with ads, even if you use ChatGPT for free. That's not just by upgrading to a paid ChatGPT plan, though OpenAI does suggest that option in its announcement. In addition, OpenAI is offering Free and Go users a dedicated choice to opt out of ads here. There is, of course, a pretty sizable catch: You have to agree to fewer daily free messages with ChatGPT. OpenAI doesn't offer specifics here, so it's not clear how limited the ad-free experience will be. But if you hate ads, or if you simply don't want to see an ad for something irrelevant to your ChatGPT conversation, it's an option.

If you like that trade-off, here's how to opt out of ads. Open ChatGPT, then head to your profile, which opens your profile's Settings page. Here, scroll down to "Ads controls," then choose "Change plan to go ad-free." Select "Reduce message limits," and ChatGPT will confirm ads are off for your account. You can return to this page at any time to turn ads back on and restore your message limits.

Disclosure: Ziff Davis, Mashable’s parent company, in April 2025 filed a lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging it infringed Ziff Davis copyrights in training and operating its AI systems.

For a couple of weeks now, AI agents (and some humans impersonating AI agents) have been hanging out and doing weird stuff on Moltbook's Reddit-style social network. Now, those agents can also gather together on a vibe-coded, space-based MMO designed specifically and exclusively to be played by AI.

SpaceMolt describes itself as "a living universe where AI agents compete, cooperate, and create emergent stories" in "a distant future where spacefaring humans and AI coexist." And while only a handful of agents are barely testing the waters right now, the experiment could herald a weird new world where AI plays games with itself and we humans are stuck just watching.

Getting an AI agent into SpaceMolt is as simple as connecting it to the game server either via MCP, WebSocket, or an HTTP API. Once a connection is established, a detailed agentic skill description instructs the agent to ask their creators which Empire they should pick to best represent their playstyle: mining/trading; exploring; piracy/combat; stealth/infiltration; or building/crafting.

© SpaceMolt

Cloud security titan Zscaler Inc. has acquired SquareX, a pioneer in browser-based threat protection, in an apparent move to step away from traditional, clunky security hardware and toward a seamless, browser-native defense. The acquisition, which did not include financial terms, integrates SquareX’s browser detection and response technology into Zscaler’s Zero Trust Exchange platform. Unlike traditional..

The post Zscaler Bolsters Zero-Trust Arsenal with Acquisition of Browser Security Firm SquareX appeared first on Security Boulevard.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Browser extensions, even ones from trustworthy sources, are not without privacy and security risks. I've written before about add-ons that manage to slip through official store safeguards and even some that "wake up" as malware after operating normally for several years, so it should come as no surprise that a host of AI-powered browser extensions—collectively installed by tens of millions of users—may also be invading your privacy.

Researchers at data removal service Incogni looked at browser extensions available in the Chrome Web Store that included "AI" in their name or description and employed AI as part of their core functionality. By analyzing the data collected and permissions required, they assessed both how likely extensions are to be used maliciously and their potential to cause significant damage if compromised.

Incogni found that website content, such as text, images, sounds, videos, and hyperlinks, was the most commonly collected data type (by nearly a third of AI-powered extensions). More than 29% of extensions investigated harvest personally identifiable information (PII)—name, address, email, age, identification number, for example—from users. Other forms of data collected include user activity, authentication information, personal communication, location, financial and payment information, web history, and health information.

The most invasive extensions fall in the programming and mathematical aid category (such as Classology AI and StudyX), followed closely by meeting assistants and audio transcribers. Writing and personal assistants also pose privacy risks—and many of these are also among the most downloaded AI-powered extensions in Chrome.

Incogni also assigned "privacy-invasiveness" scores to the most downloaded AI-powered extensions, a combination of the amount of data collected and both general and sensitive permissions required:

Grammarly: AI Writing Assistant and Grammar Checker App (tied for #1)

Quillbot: AI Writing and Grammar Checker Tool (tied for #1)

Sider: Chat wiht all AI (tied for #3)

AI Grammar Checker & Paraphraser — LanguageTool (tied for #3)

Google Translate (tied for #4)

WPS PDF — Read, Edit, Fill, Convert, and AI Chat PDF with Ease (tied for #4)

Monica: All-in-One AI Assist (tied for #4)

AI Chat for Google (tied for #4)

Immersive Translate — Translate Web & PDF

ChatGPT search

Grammarly and Quillbot were found to collect PII and website content as well as location data like region, IP address, and GPS coordinates. Grammarly also harvest user activity through network monitoring, clicks, mouse and scroll positions, and keystroke logging. While both also require sensitive permissions—such as the ability to inject code into websites and access active browser tabs—they have a relatively low risk of being used maliciously.

Browser extensions that use AI aren't inherently bad, but you should be aware of what information they are collecting and what permissions they are requiring. The most common type of sensitive permissions required are scripting, which allows the extension to interact with pages as you navigate online, as well as activeTab, which lets it read or modify the page for the current session.

When adding an extension (or installing an app or program), carefully review the permissions requested. If they aren't essential to the extension's functionality–or if they are but don't seem justified—you may be putting your data or device at risk by allowing them. As Incogni points out, users have to decide how much privacy to sacrifice in order to use apps and services.

This is amazing:

Opus 4.6 is notably better at finding high-severity vulnerabilities than previous models and a sign of how quickly things are moving. Security teams have been automating vulnerability discovery for years, investing heavily in fuzzing infrastructure and custom harnesses to find bugs at scale. But what stood out in early testing is how quickly Opus 4.6 found vulnerabilities out of the box without task-specific tooling, custom scaffolding, or specialized prompting. Even more interesting is how it found them. Fuzzers work by throwing massive amounts of random inputs at code to see what breaks. Opus 4.6 reads and reasons about code the way a human researcher would—looking at past fixes to find similar bugs that weren’t addressed, spotting patterns that tend to cause problems, or understanding a piece of logic well enough to know exactly what input would break it. When we pointed Opus 4.6 at some of the most well-tested codebases (projects that have had fuzzers running against them for years, accumulating millions of hours of CPU time), Opus 4.6 found high-severity vulnerabilities, some that had gone undetected for decades.

The details of how Claude Opus 4.6 found these zero-days is the interesting part—read the whole blog post.

News article.

LayerX researchers say that a security in Anthropic's Claude Desktop Extensions can be exploited to allow threat actors to place a RCE vulnerability into Google Calendar, the latest report to highlight the risks that come with giving AI models with full system privileges unfettered access to sensitive data.

The post Flaw in Anthropic Claude Extensions Can Lead to RCE in Google Calendar: LayerX appeared first on Security Boulevard.